Dealing With Spiky Traffic and Thundering Herds

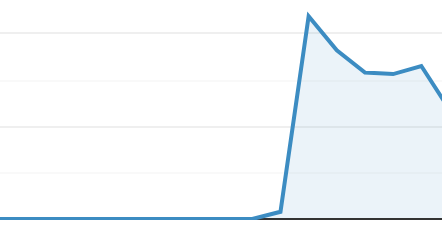

The graph above is a concurrent user count screenshot taken over the course of a few minutes. We can look at it in a couple ways. The first is excitement: more users! This feeling usually lasts until the infrastructure comes crashing down to reality. At that point the feeling of excitement might be replaced with panic. How do we keep the servers from collapsing if this keeps happening?

Dealing with a 10-100x increase in users is hard - especially if you run an app where spikes are a frequent occurrence. With the advent of push notifications and live streaming these traffic patterns are becoming more and more common. This is a thundering herd: users stampede your services - often taking down everything in their path.

The first thing that goes down is usually the database. Thousands of queries hit the database at once and trigger a massive slow down. It’s not uncommon for the database CPU graph to look just like the graph above. When the database slows down, requests start timing out. Timeouts and long requests overload the application servers. Soon everything is falling over. Not good.

We need to stop the herd (or at least slow it down). This brings us to step one:

Cache Liberally

When load on the database is spiking from a slow or frequently used query, the easiest way to solve the issue is to throw the data in a cache. We can use a tool like Redis for this - or take it one step further and cache the data on the edge using a CDN like Cloudflare or Cloudfront.

The advantage of a CDN is that the request will never hit our service. Even when traffic increases by 100x our service will hum along as if nothing changed.

For many services, using a cache will be enough. But for others, the thundering herd results in so many concurrent users that when the cache expires, we end up with the same problem all over again.

Since there are so many concurrent users, for every cache miss that occurs, all requests will be let through during the time that the cache value is being recalculated. The underlying service will collapse in response to this.

So how do we stop all these requests from coming through?

We Need to Close the Gate

Clearly our underlying server cannot handle this much traffic. We need to “close the gate” and not let the requests in. Of course, this alone won’t work. We still need to serve something!

The key insight here is that every request is asking for the same data. Instead of letting them all through the gate, let’s only allow one request through to recalculate the data. After all, the data will be the same for every request.

Now, what do we do with all the other requests?

Option 1: Serve the Others Stale Data

Serving stale data has the advantage of being relatively simple and fast. The idea here is that we serve the old data in the cache while we’re recalculating the current up-to-date data.

Using a cache like Redis or Memcached, this would look something like the following:

- Store a key in the cache with a fake, longer than desired expire time.

- In this key, store both the data and the real cache expire time.

- On fetching the key, check the real expire time. If it has expired:

- Update the real expire key to be in the future (this will prevent other requests from attempting to recalculate the data).

- Recalculate the data and then update the key with the latest data, so all subsequent requests will get the latest data.

If possible, the read and update steps should be done in an atomic way. This will prevent any other request from recalculating the data at the same time.

Option 2: Have the Others Wait for the Latest Data

We can also have the other requests wait for the latest data from the request. This is called request coalescing or request collapsing. Many CDN providers have this functionality built in (often in advanced settings).

Using something like Redis or Memcached to solve this problem would look like the following:

- Attempt to get a key from the cache.

- If key is not there, then attempt to acquire a lock on the data with the Redis key as the lock name (one option here is to use a distributed lock with multiple servers).

- If the lock is acquired, then recalculate the data and refill the cache.

- If the lock is not acquired, wait for the lock to be available again and check if the cache has been filled - if it has, another request has already done the recalculation! Return that data.

A queue is another popular way to tackle this problem. See the resources below for ideas there.

Conclusion

And with that, the requests are satisfied! Next time a massive spike in traffic occurs, our servers will have enough breathing room from the cache to safely scale up and our database will live to see another day.

That is, until we have to deal with data that can’t be cached globally… perhaps that’s a problem for another day.

Resources

Source for GIFs on this Page: Video from Facebook Engineering on Thundering Herds

Apache Traffic Server Ticket for Handling Thundering Herds

Break up the Memcache Dogpile on High Scalability